- Home

- Christina Gonzalez

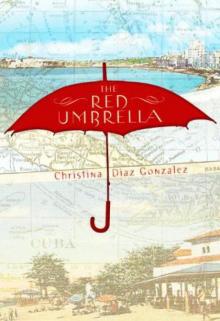

The Red Umbrella

The Red Umbrella Read online

For my sons, Peter and Daniel

Chapter 1

CASTRO RULES OUT ELECTIONS IN CUBA

—THE NEW YORK TIMES, MAY 2, 1961

I watched as a white heron circled the beach and then headed north toward the open waters of the tropics. The lone bird flapped its wings, gradually disappearing into the pink-and-orange-streaked sky. It was time for us to go, too.

“Pack it up, Frankie. It’s getting late,” I said.

Frankie threw his small fishing net into the rolling surf. “C’mon, Lucía … a few more minutes. We don’t even have school tomorrow.”

I sighed and leaned back on my towel. Frankie was right, there was no need to rush home. Since all the private schools had been closed and the public schools were being reevaluated, who knew when classes would start again. I was growing tired of constantly hearing about the revolution, but I privately thanked Castro for postponing my algebra test. I closed my eyes and imagined old Señora Cardoza, our eighth-grade teacher, being questioned by one of the new government officials. The poor woman would probably be so flustered that she’d pass out. Then I thought of Manuel, who sat two rows ahead of me in algebra class. With his light brown hair and green eyes, he was definitely the cutest boy in class. Maybe that’s why I couldn’t concentrate on anything Señora Cardoza said.

A distant rumbling snapped me out of my daydream. I searched the sky to see if a storm was coming, but it was a clear evening. The thunder-like noise grew. Something big was coming down the beachside road. I shook the sand off my feet, grabbed my sandals, and hurried toward the boardwalk. A caravan of large camouflaged trucks and jeeps came into view. I half hid behind a coconut palm and watched as truck after truck, filled with men wearing fatigues, roared past me. During the past year, there had been pictures of the revolution’s soldiers in the newspapers and on TV, but I’d never seen so many in person. Most of the soldiers that were riding in the trucks looked like they were in their twenties, but a few seemed to be my age. One of them had such intensity and fierce determination in his eyes that it made me shudder, and I quickly looked away.

And then they were gone, leaving behind a cloud of sand and dust in the road.

“Did you see that?” Frankie yelled from the water’s edge.

I turned and walked back to where my bike and beach towel lay. “Yeah. Strange to see army trucks around here.”

“Huh? I’m talking about the huge yellowtail that swam …” Frankie pulled in his net and spun around. “Wait, those were army trucks?”

“Yeah, but they’re already gone.” I shook out my towel and carefully tucked it into the bike’s front-hanging basket. “Vámonos, Frankie, we’re going to be late for dinner.”

“You sure they’re gone?” Frankie looked toward the road.

“I’m sure. Nothing ever happens in Puerto Mijares. Those soldiers were probably just driving through.”

“Well, you can go home. I’ll catch up later.” He stared at the waist-deep water surrounding him.

“Ha! Mamá would have my head if I left you alone.”

“I’m already seven. I don’t need a babysitter.” He twisted his body, getting ready to throw the net again.

Frankie could be stubborn, but I knew the one thing my little brother loved more than fishing. “Okay, I guess we’ll both have to miss Mamá’s flan.”

“¿Flan?” Frankie pulled at the net, already in midair, catching it with his left hand. “Why didn’t you say that before?” He sprinted out of the water and hurried over to his bike. A sly smile crept onto his face. “Hey, Lucy,” he said, and with one swift move, he snatched my towel and threw it as far as he could. “Race you home!”

* * * * *

My bike screeched into the driveway. I jumped off, hurdled the potted plant sitting by the porch steps, and ran to the front door. “Beat you again,” I laughed, stumbling into the house.

An eerie silence greeted me.

“Mamá? Papá?” I called out. There was an uneasiness hanging in the air as I walked into the darkened family room.

Frankie clattered into the house. “You only won because I let you.”

“Shhh. Something’s wrong,” I whispered.

“¿Qué?”

“Not sure.” I headed toward the dimly lit kitchen.

My parents were sitting at the kitchen table huddled around a radio, oblivious to the fact that the sun had set and that most of the house was now dark and full of shadows.

“Oh, hijos, you’re home.” Mamá immediately stood up, smoothed back her dark hair, and gave us quick kisses on the cheek. She signaled for Papá to turn down the radio. The voice of someone giving a speech was promptly silenced.

“What’s going on? Why is the house so dark?” I asked.

Mamá turned on some lights and took out the dinner plates.

“Nothing’s happened.” Papá smiled, but the worried look in his eyes betrayed him. “Your mother and I just lost track of time listening to the radio. Did you have fun at the beach?”

“It was okay, but I didn’t catch anything. I did see this huge yellowtail … about this big!” Frankie opened his arms wide.

Papá chuckled. “That big, huh? Probably more like this.” He brought Frankie’s arms together until they were about a foot apart.

“Well, yeah, maybe.” Frankie reached for the plate of sliced avocado.

“Mamá, do you need help with dinner?” I asked, peering over her shoulder to see what she was cooking.

“No, it’s just leftovers from yesterday.” She turned as Frankie went for his second slice. “Frankie, no comas más. You’ll get filled up before dinner. Now wash up … both of you. Dinner will be ready in five minutes.”

“You made flan, right?” Frankie wiped his sticky hands on his shorts.

“Oh, the flan. I forgot, with everything—”

“Ahem.” Papá cleared his throat.

“I’ll make it tomorrow, sweetie. Promise. Now go.”

“Told you we shouldn’t have left the beach,” Frankie muttered as we stepped into the hallway.

I ignored him and focused instead on the shouting coming from the kitchen radio. Mamá had raised the volume the moment we’d left the room. A reporter was describing a large crowd gathered near the town square, and in the background there was some sort of chanting. I strained to hear what they were saying. Then the words came through clearly, echoing in my head. ¡Socialismo o muerte! Socialism … or death!

Chapter 2

U.S. BRANDS CUBA COMMUNIST STATE, SAYS CASTRO OUTDOES SOVIET IN BARRING VOTE, LIKENS HIS RALLIES TO HITLER’S

—THE NEW YORK TIMES, MAY 3, 1961

“Today I’m having real fun,” I mumbled to myself.

I pulled open the bedroom drapes and took a look outside. The brightness of the morning sun blinded me for a moment. Then, as my eyes adjusted to the light, I realized what a perfect day it was. The cloudless sky, the slight chatter of birds in the fruit trees, and the warm breeze that brushed past my cheek … there was no place I’d rather be, although Ivette and I did talk about visiting Paris or Rome someday. We’d been best friends since kindergarten, and I couldn’t imagine exploring those cities without her. But for now, we’d have to be happy spending the day walking around downtown Puerto Mijares. We could catch a movie or even a double feature. Something by Fellini was probably playing.

I thumbed through my closet and picked out a pleated emerald-green skirt with a crisply ironed white shirt. It wasn’t too fancy or too casual. After all, you never knew who we might run into in town. But choosing a headband was a bit harder. I loved my bright yellow one, which would stand out against my dark hair, but the green and white polka-dot one matched my outfit perfectly. This was a decision better left for Ivette. Sh

e was my fashion guru.

A thumping on the stairs let me know that Frankie was on his way to the kitchen. The warm, sweet smell of café con leche had wafted its way up to me, and my stomach growled in response. Breakfast was probably already on the table.

I wondered if everything was back to normal after the strangeness of the night before. The house had felt so quiet, and it was odd for both Mamá and Papá to choose to hear news reports on the radio instead of watching TV with us. But the bright sun chased away those shadows. Why worry when the day held so many possibilities? I grabbed my pink robe and headed downstairs before Frankie could devour everything Mamá had made.

“Mamá, today I’m catching the biggest fish in the ocean. I can feel it,” Frankie said, stuffing a freshly fried croqueta in his mouth.

“Buenos días.” I walked into the kitchen to find Mamá slicing a loaf of bread.

“Oh, Lucía, you’re up. Good, I was waiting for you to come downstairs. I need to talk to the two of you.”

I stopped in my tracks. Babysitting Frankie the day before was one thing, but spending the entire school break with a seven-year-old was completely unfair. This unexpected vacation was supposed to be enjoyed with my friends. I looked for Papá, who usually agreed with me. There were only two plates on the table, and the white serving platter in the middle held only six small, ham-filled croquetas, barely enough for Frankie and me.

“Where’s Papá?” I asked.

“He had to go to work early.” Mamá put down the knife and walked over to the table. “I have a favor to ask the both of you. It’s about—”

“So he already left?”

“Yes, they called him from the bank early this morning.” Mamá pointed to the chair next to Frankie. “Mi hija, siéntate.”

A wave of disappointment came over me. I was going to get stuck with Frankie again. He’d tag along all day as Ivette and I walked around downtown. I sank into the seat next to my brother.

“Niños, it’s about the revolution. You know things in Cuba have changed, especially in the last few months.”

Air. I felt like I could breathe again. This was a talk about the revolution and not about more babysitting. I smiled at my mother. “Mamá, we know. We hear about it in school all the time.” I took the same nasal, monotone voice of my revolution-loving social-studies teacher. “Comandante Fidel is making our lives better. He has replaced corruption with a new system of government that has brought much happiness to all the Cuban people. We are living in a great time. Everything will be fair and equal for all citizens.”

“Well, it’s not really about being fair. That’s why I wanted to—”

“It is fair. Señor Pedraza, our new principal, showed us.” Frankie reached for some orange juice.

“Eh? What do you mean he showed you?” Mamá raised one of her perfectly drawn eyebrows.

“Señor Pedraza showed us with a secret experiment.” Frankie took a big sip of juice. “Last week, before the school closed, he had us all pray that everyone would have ice cream when they got home. He told us to pray really hard … and I did, because you know how much I love ice cream.”

“Mmm-hmm,” Mamá answered as Frankie grabbed another croqueta.

“So, everybody prayed, but the next day, only a couple of kids said they had any. Señor Pedraza said that didn’t seem very fair.”

I laughed. “Yeah, but that’s because—”

“I’m not done with my story!” Frankie glared.

“Sigue, tell me what happened next.” Mamá spun her wedding ring around her finger. The diamond disappeared and then reappeared with each turn.

Frankie took a deep breath and turned back to Mamá. “Well, Señor Pedraza told us to close our eyes again and this time to ask Comandante Fidel for ice cream. A few minutes later, a lady brought enough for the whole class. Señor Pedraza said that El Comandante wouldn’t leave anyone out. If one kid was going to get ice cream, then it was only right that we all got some. Now, I think that was super fair.” Frankie licked the croqueta crumbs off his fingers.

Mamá shook her head. “It’s not so simple.”

“Yeah, goofball. God doesn’t give you everything you ask for … if He did, I’d be allowed to wear makeup.” I gave Mamá a playful look.

“All I know is that we got to eat ice cream, and that never happened when Padre Martín was in charge.”

“But you understand that Fidel isn’t better than God, right, Frankie?” Mamá asked.

Frankie slowly nodded.

Mamá stopped playing with her ring and rubbed her hands together. “I thought this whole Fidel thing would’ve been over by now. That everything would return to normal in time, but …”

I poured myself some café con leche. “Don’t worry, Mamá. Nothing really changes around here.”

Mamá bit her lip and shook her head. “No, Lucía, things have changed … in big ways, even here.” She paced around the kitchen. “First they kick out the priests, then they close the schools, and now …” Mamá paused to watch the orange-striped curtain flutter in the kitchen window. She nodded as if in response to some silent question. “Your father and I have decided that you two need to stay home for the next few days.”

“What? But there’s no school!” I couldn’t believe what Mamá was saying.

“I know, but your father and I talked it over.”

“What about if we go together to the beach? We were there yesterday,” Frankie argued.

Mamá combed his hair with her fingers. “Mi hijo, it’s not safe. I don’t want to get into it right now, so just do this for me and stay inside. Understood?”

Frankie crossed his arms and pulled away from Mamá’s touch.

I thought for a moment. “Does this have to do with the soldiers that drove by the beach yesterday? Is that what has you worried? It’s not that big a deal. We don’t have any anti-revolutionaries in Puerto Mijares. Nothing will happen.”

Mamá’s jaw dropped and she quickly made the sign of the cross. “You ran into them? ¡Dios mío!”

I rolled my eyes. “So that is why you’re acting like this!”

“You don’t know …” Mamá looked away.

“But I have plans with Ivette. I have to go out!”

“Ivette can come over here,” Mamá offered.

I pushed back my chair. “What for? To be a prisoner with me? Ivette wants to go downtown, go to the movies, hang out at the beach. No one knows when we’re going to have to go back to school; we have to take advantage of the time now.” Anger rose in my chest as I saw that Mamá was not going to change her mind. “You convinced Papá to do this, didn’t you?”

“No, Lucía, he’s actually the one—”

“You always treat me like a little kid, like Frankie. You won’t even let me cut my hair!”

“Lucía, you have such beautiful long hair, cutting it would be a disgrace. A few inches shorter would be fine, but why cut it to look like everyone else?”

“But it’s my hair!” I tried one last time. “Mamá, please, let me go with my friends today.”

Mamá shook her head. “I said no.”

“Call Papá,” I demanded.

Mamá raised her hand to end the discussion. “No. Your father and I both agree on this. I don’t ask much from either of you, but you will do as I say.” Her voice got a little louder. “Now promise me that you will not leave this house. Promise me!”

Frankie nodded.

“Lucía?”

It was pointless to argue.

“Fine,” I muttered.

* * * * *

My fun-filled day dragged slowly by as the morning blended into the afternoon. I had called Ivette right after breakfast and pretended to be sick. I didn’t want to admit that I was being held hostage by my irrational mother.

“Listen,” Frankie called out from the window seat, where he’d been reading a comic book. “Did you hear that?”

I walked over to him. Something was causing the window to rattle.

“It’s them, isn’t it?” he asked. “The soldiers.”

“I don’t know.”

Frankie glanced around. He pointed toward the back door.

I paused to consider it, but then shook my head. “Mamá doesn’t want us outside. We might get caught.”

“C’mon, it’s just the yard. We’ll just go, take a look, and then sneak back in. Mamá is upstairs cleaning our rooms. She’ll never know.” Frankie tossed aside the comic book and stood up.

I grabbed him by the arm. “We promised.”

“I had my fingers crossed.”

“We don’t know what’s out there.”

“Exactly!” Frankie twisted around and broke free of my grasp.

“Francisco Simón Álvarez, get back over here!” I said in my loudest whisper. “Or I’ll tell Mamá.”

“Fine, be a tattletale. But I’m still going, and it’ll be your fault if something happens because you let me go by myself.” Frankie dashed out the back door.

I had to make a decision. Keep my promise or follow Frankie. What if there was some sort of danger and Frankie got hurt because he was alone? I stopped thinking and darted out the door.

Chapter 3

NON-CUBAN PRIESTS TO BE EXPELLED, SAYS CASTRO

—THE MIAMI HERALD, MAY 3, 1961

“I think the noise is coming from over there.” Frankie pointed toward the high school up the street before sprinting past the front of the house.

I glanced around the neighborhood. It was strange that barely anyone was outside. “He’s going to get us into so much trouble,” I said to myself as I ran low to the ground so that Mamá wouldn’t see me.

Soon I caught up to Frankie. He already had his eye pressed against a hole in the school’s tall wooden fence.

“Okay, let’s go.” I tapped him on the shoulder. “Mamá is going to kill us if we get caught.”

He flicked my hand away. “Whoa, wait till you see this!”

The Red Umbrella

The Red Umbrella